The political situation in Poland has been particularly violent and repressive for queer communities since the 2015 parliamentary election. How have art institutions expressed their support?

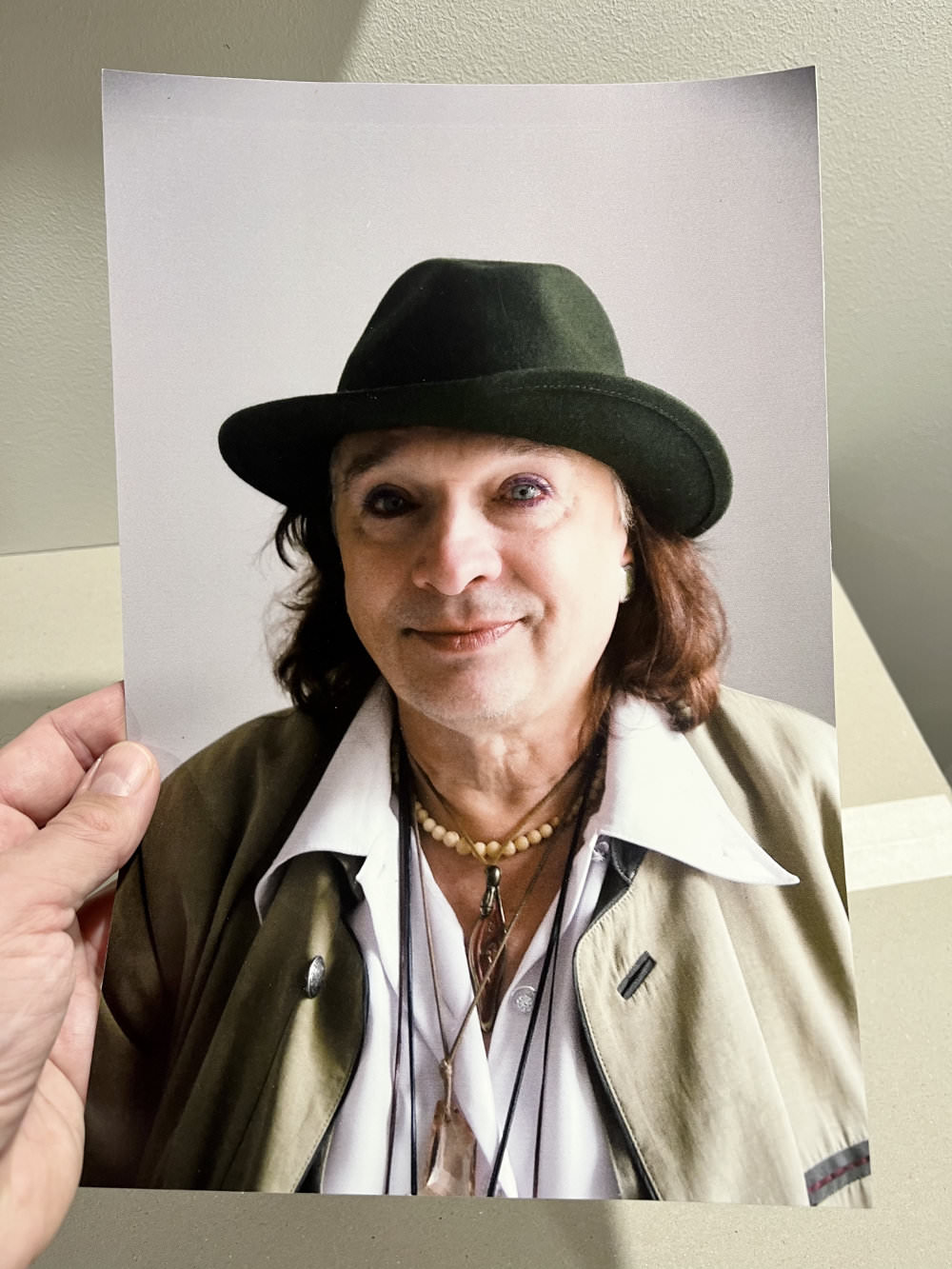

Karol

Radzisewski

QAI

X

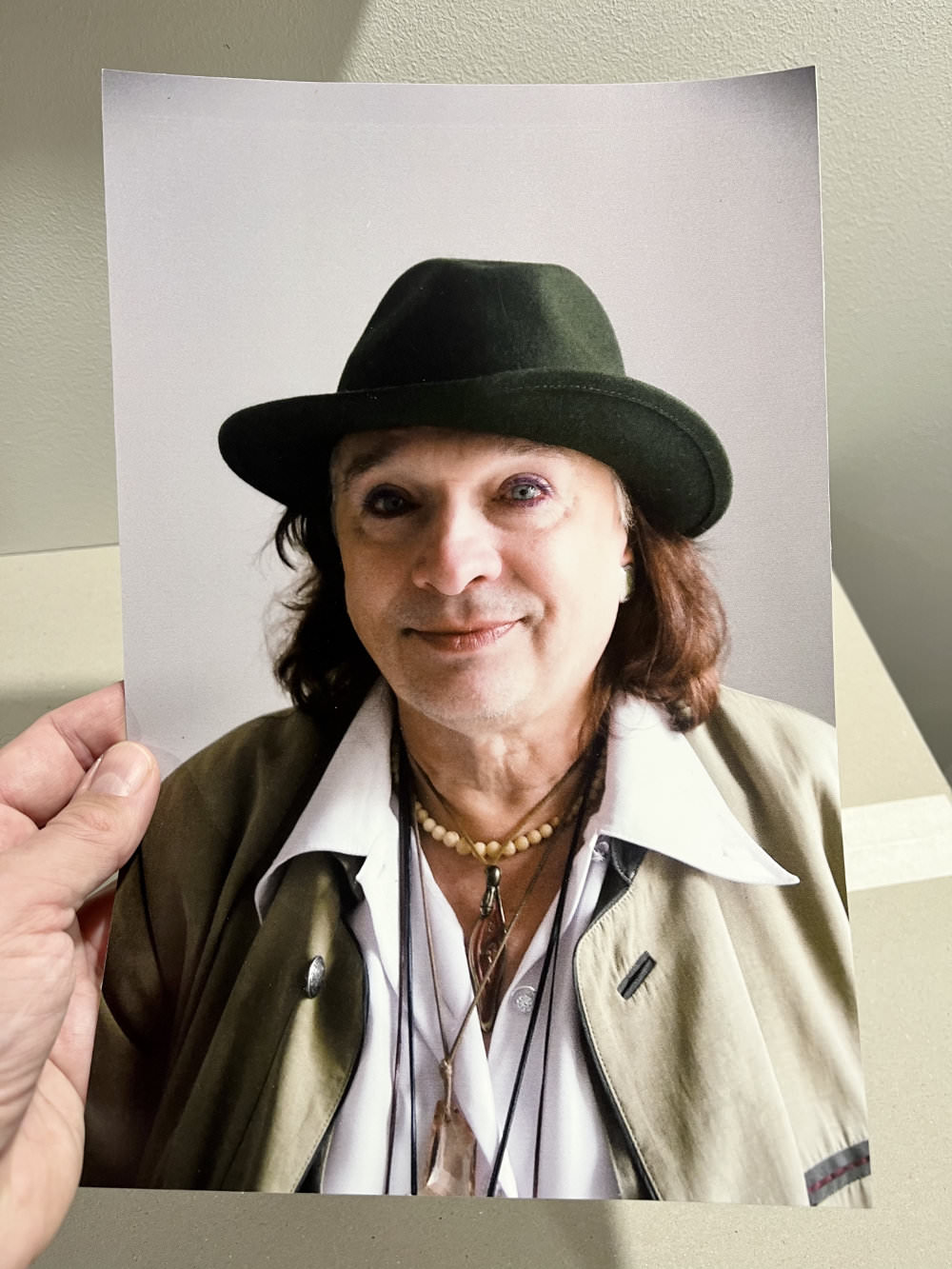

Théo-Mario

Coppola

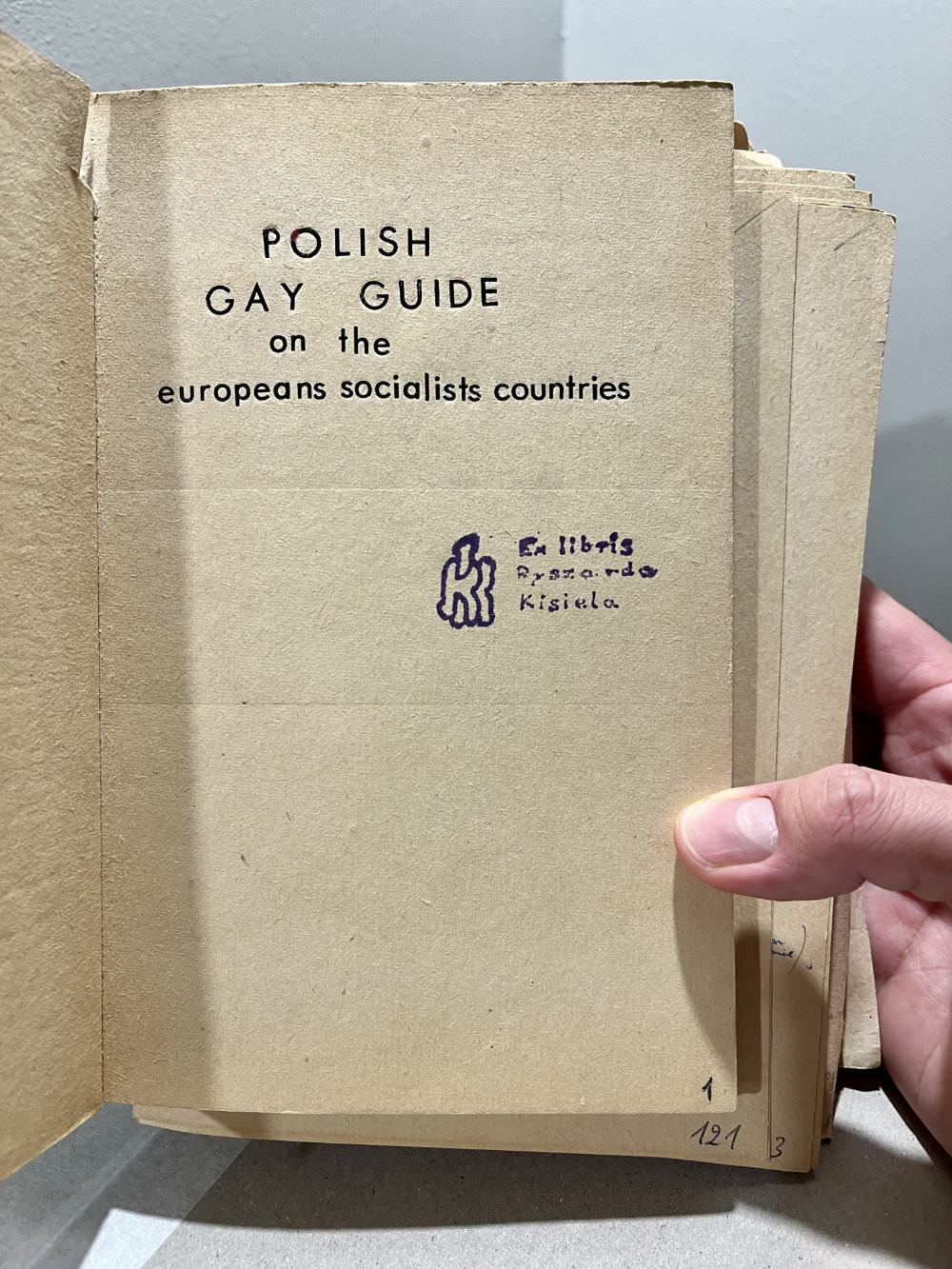

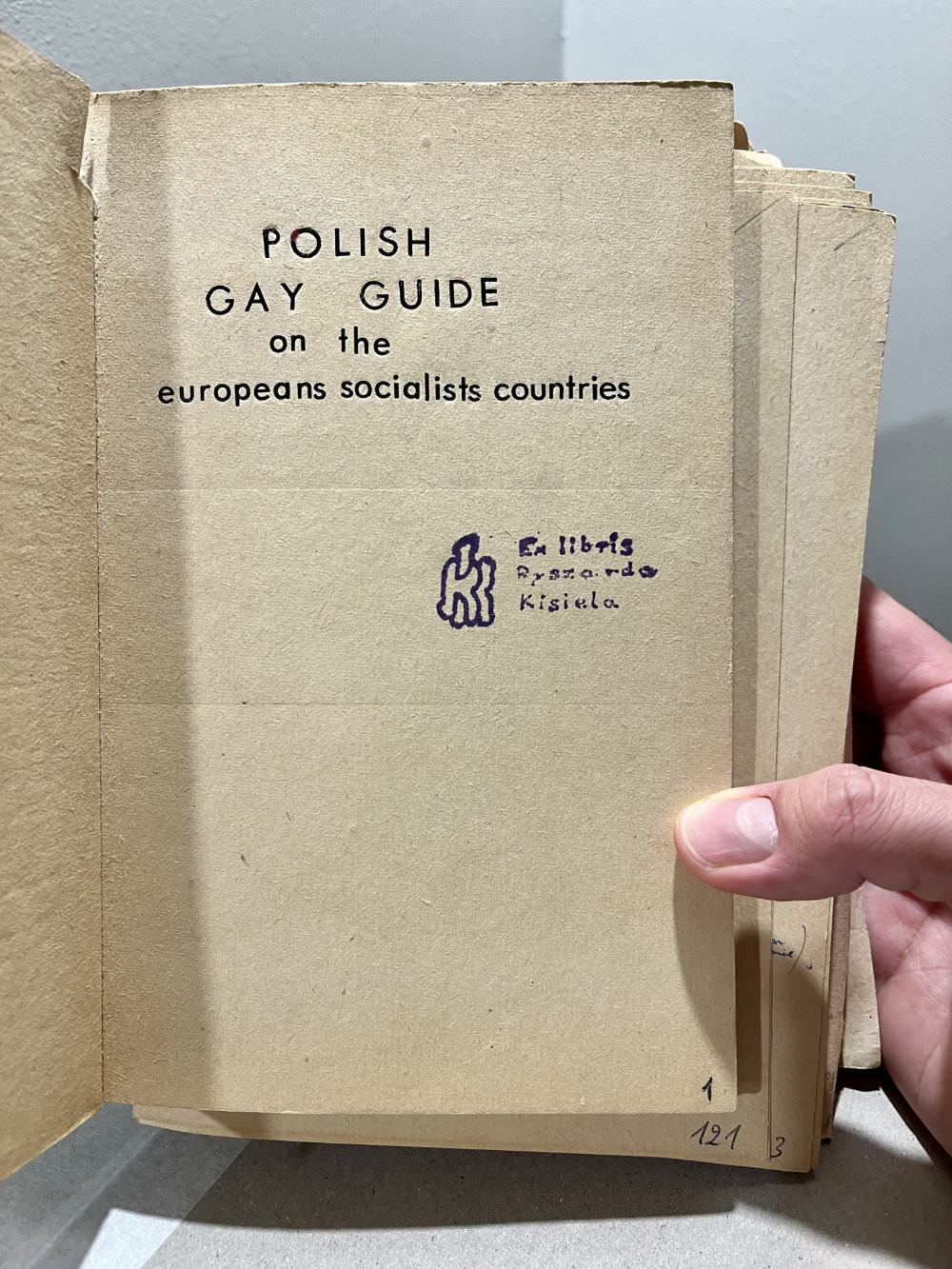

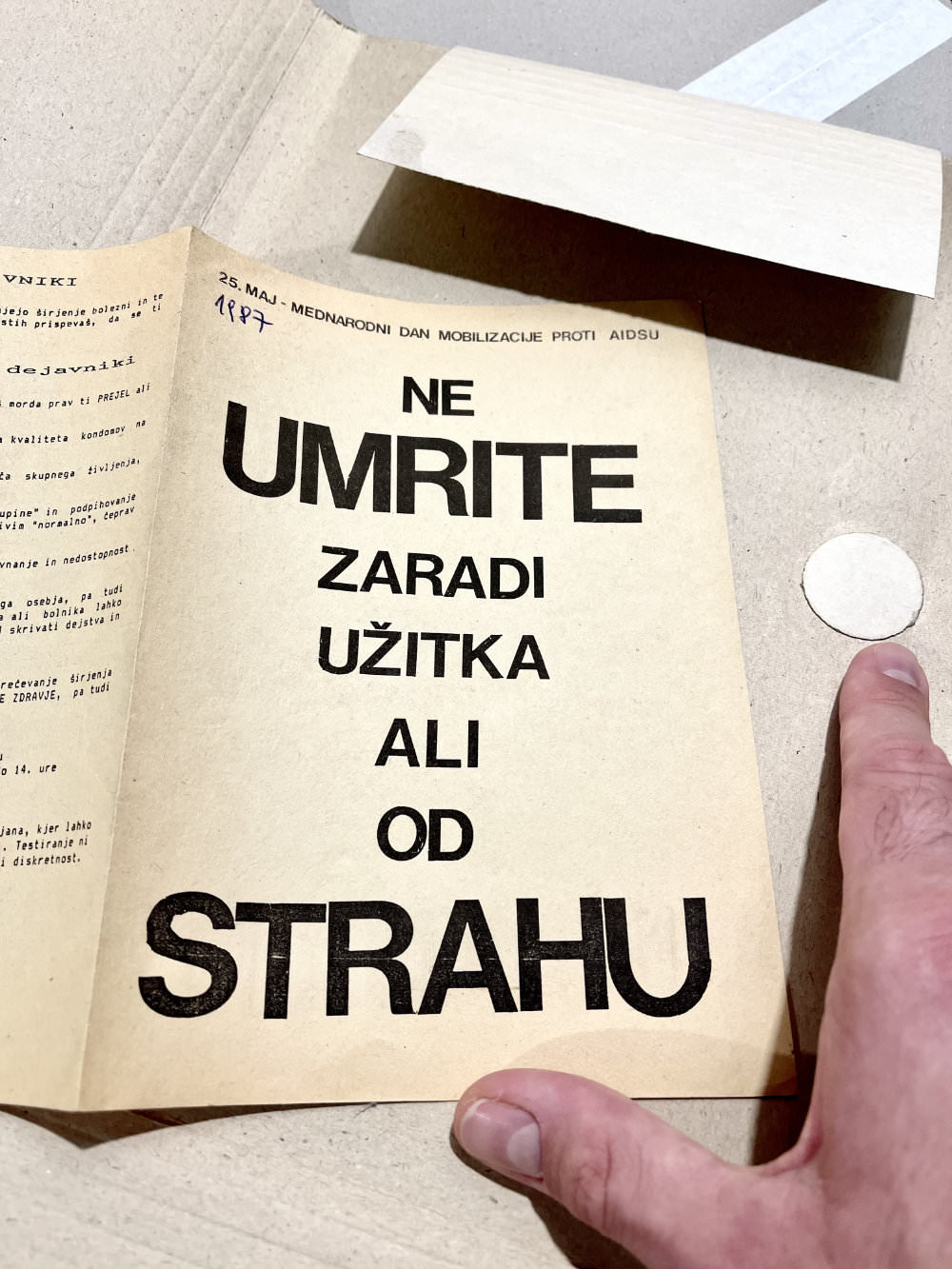

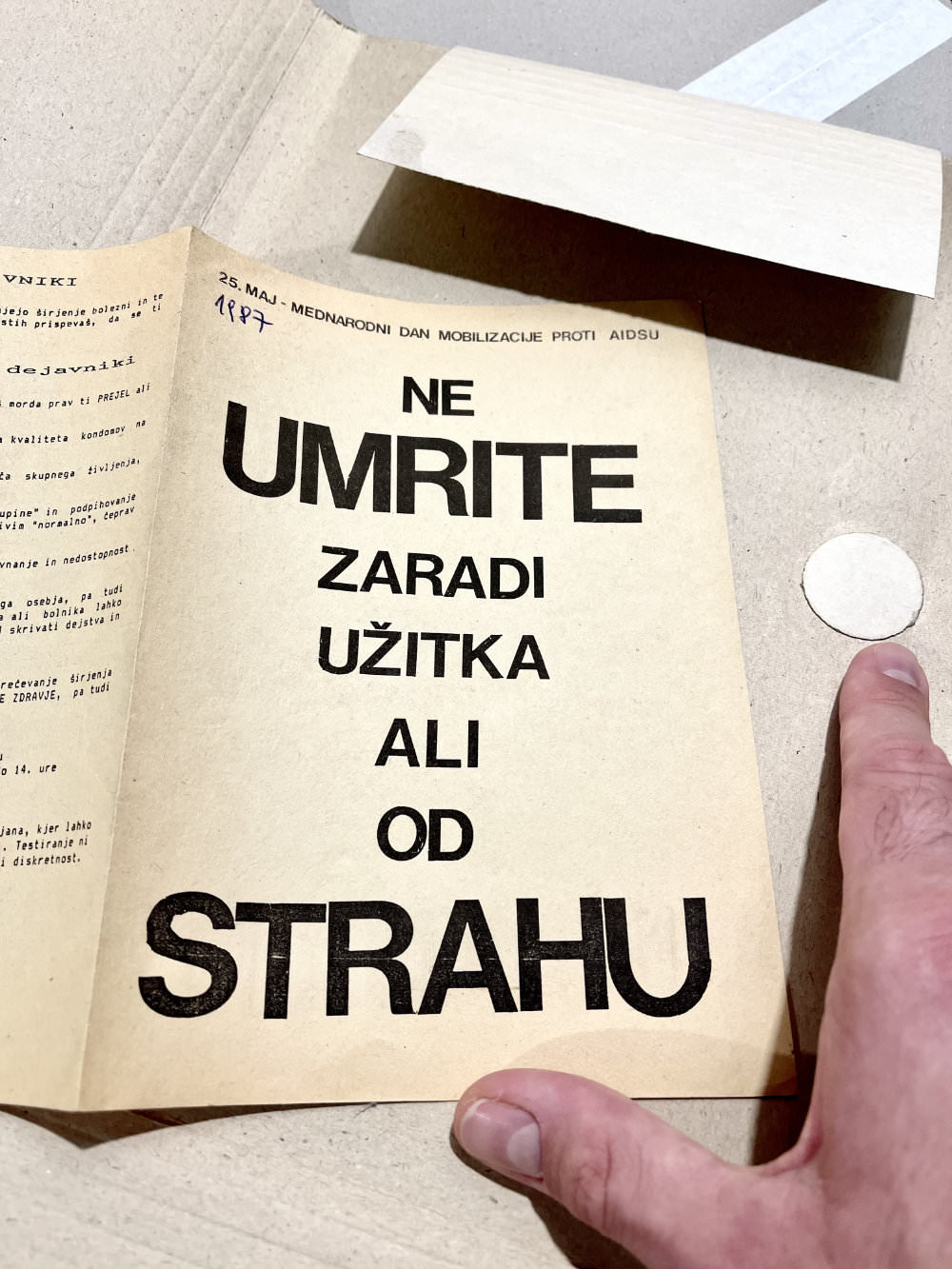

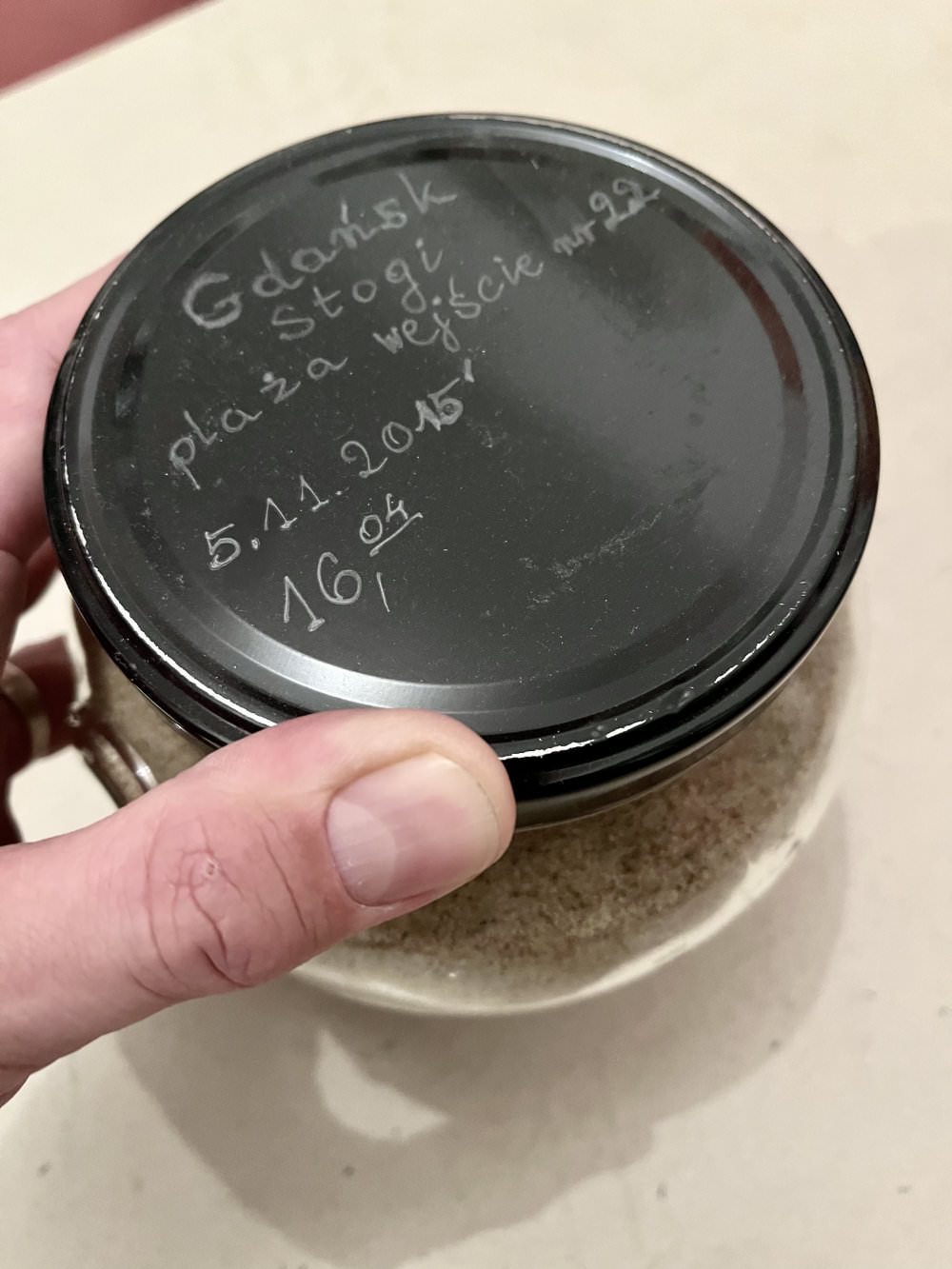

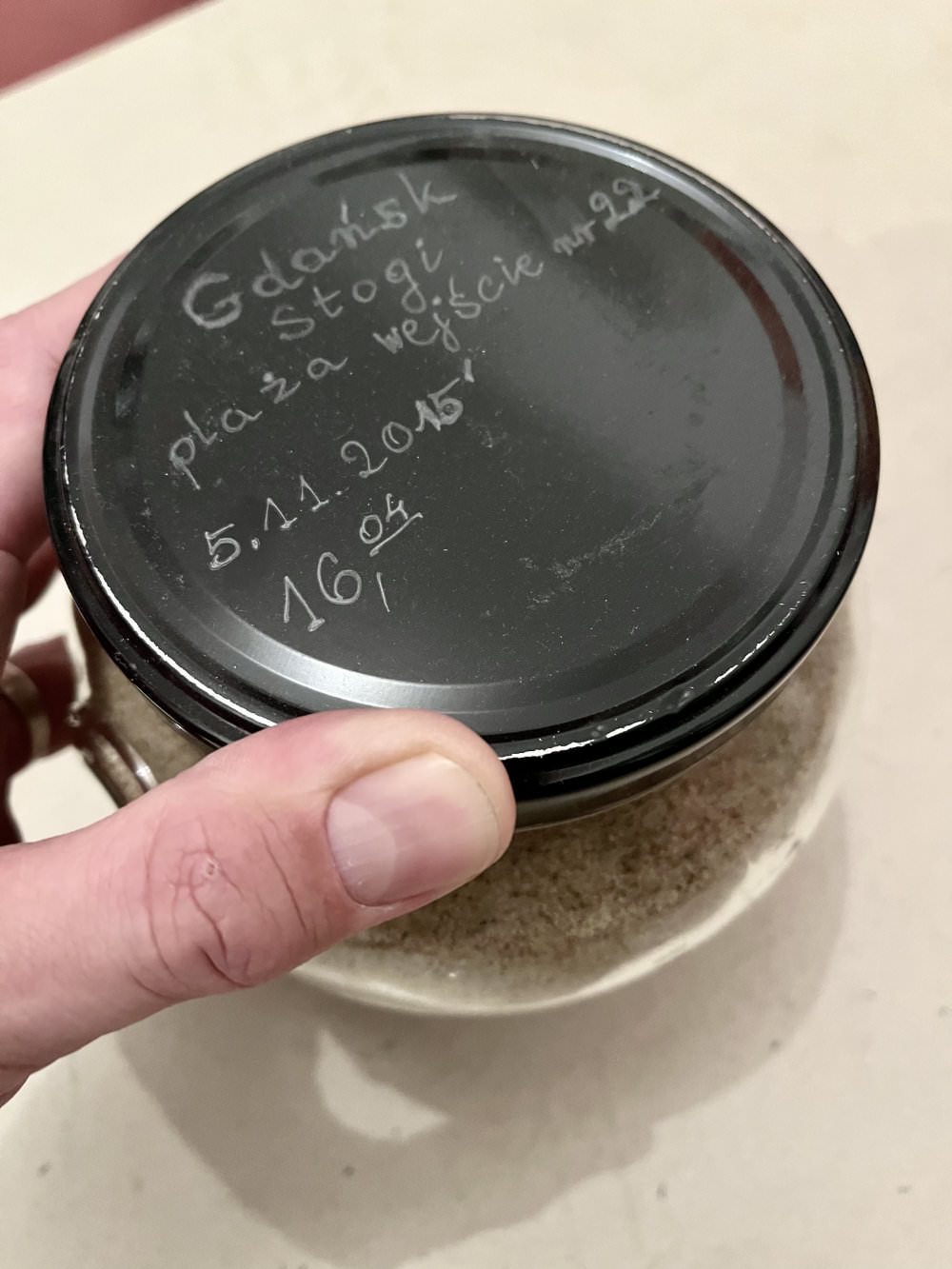

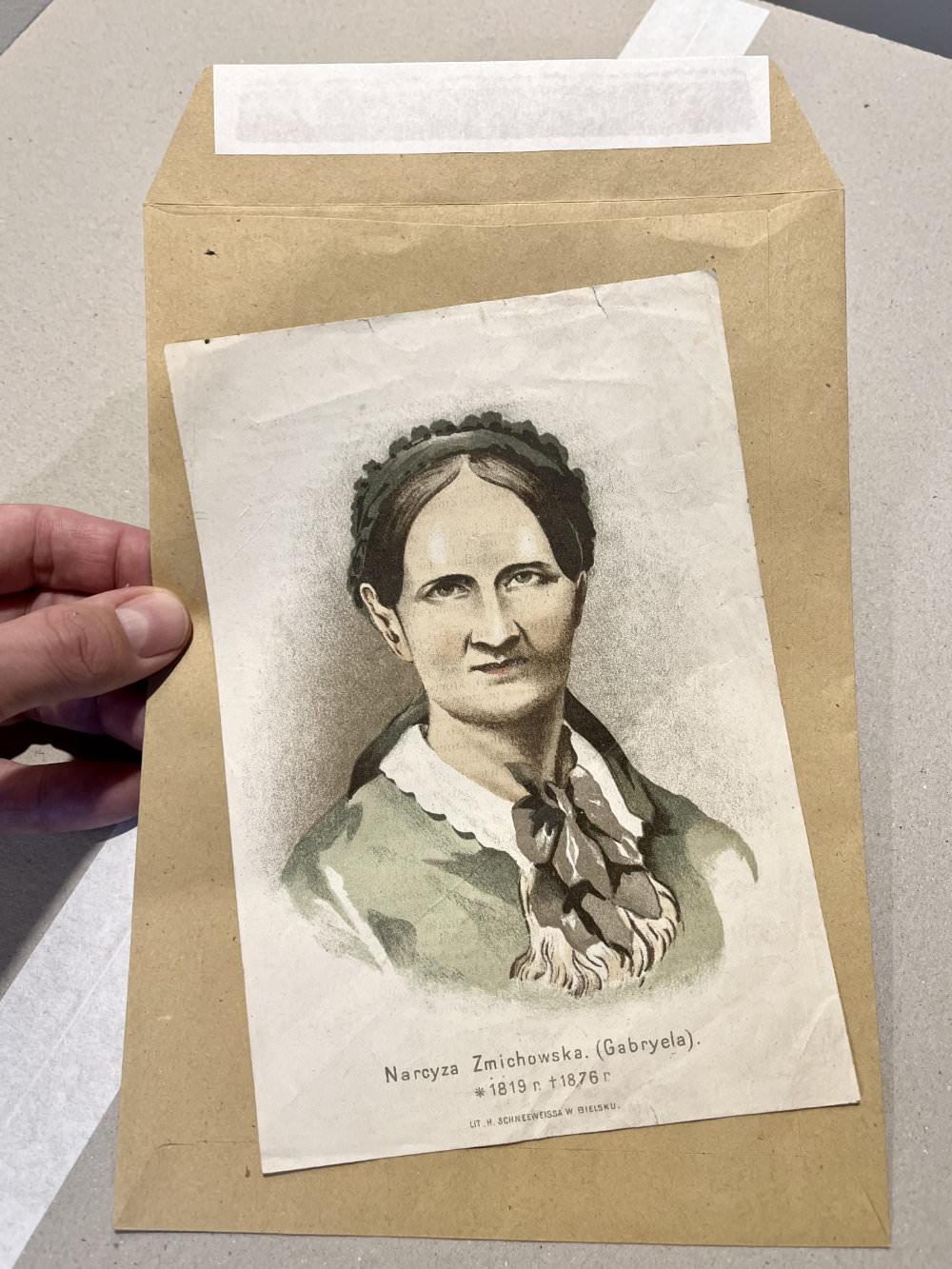

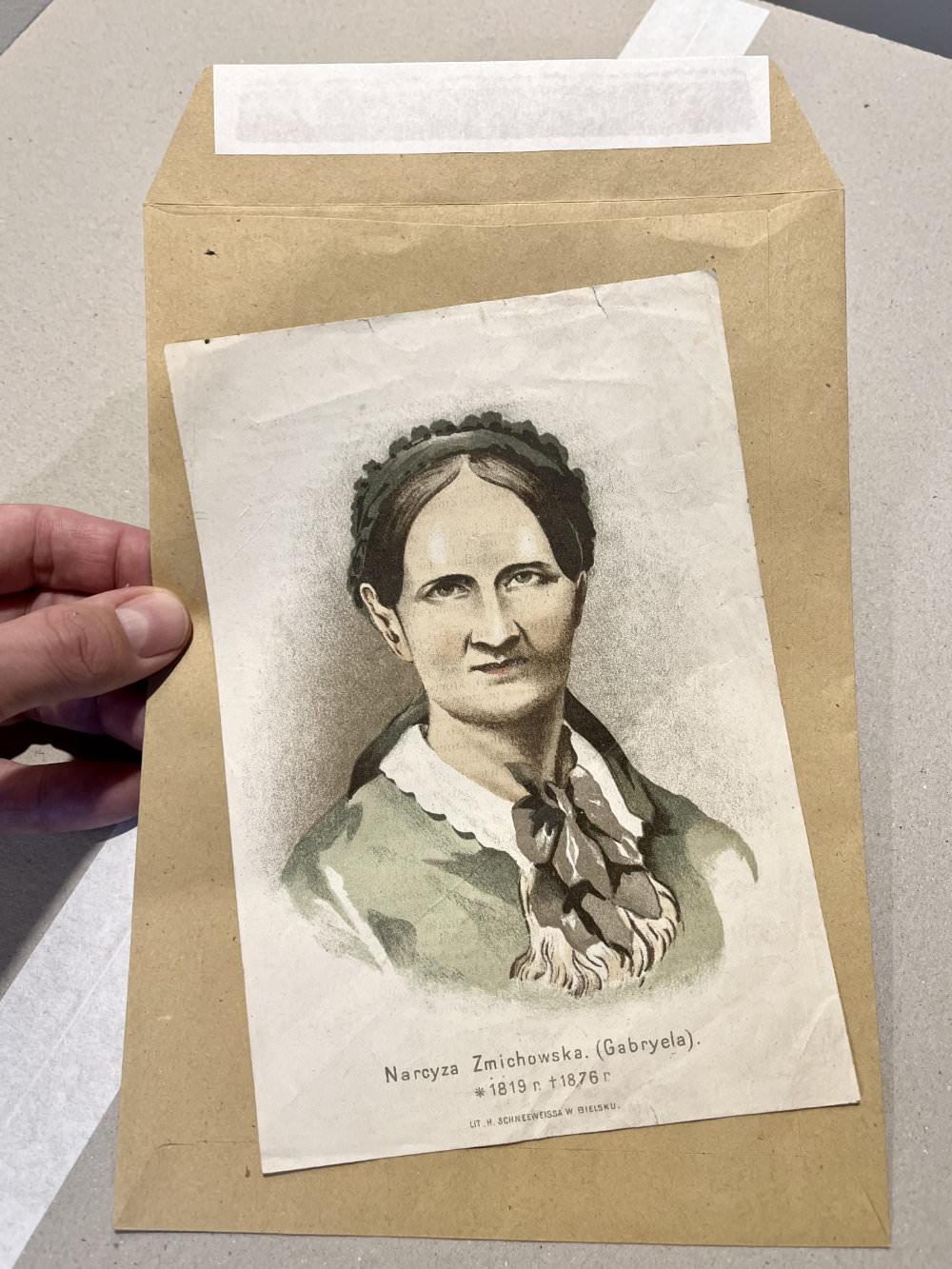

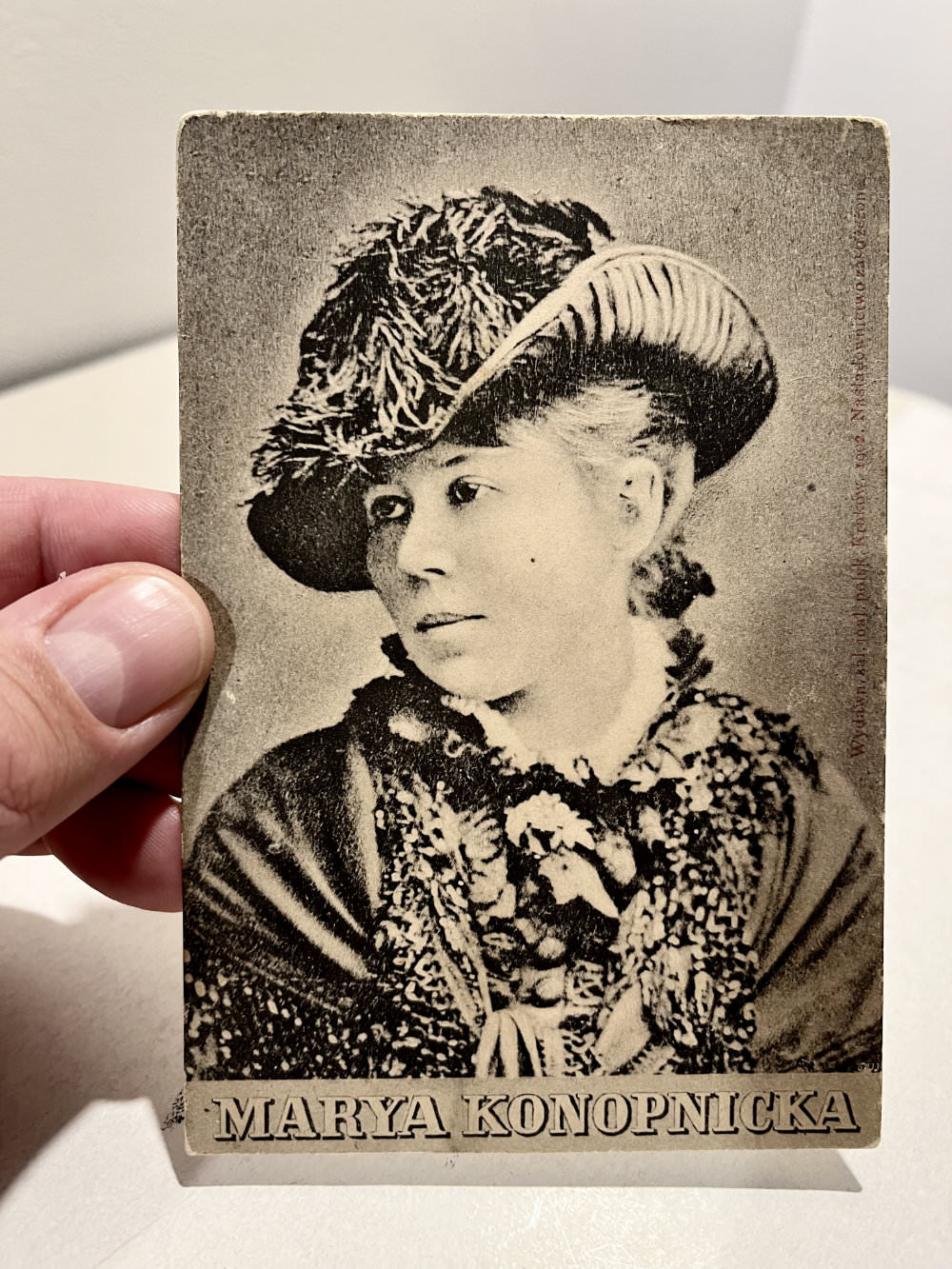

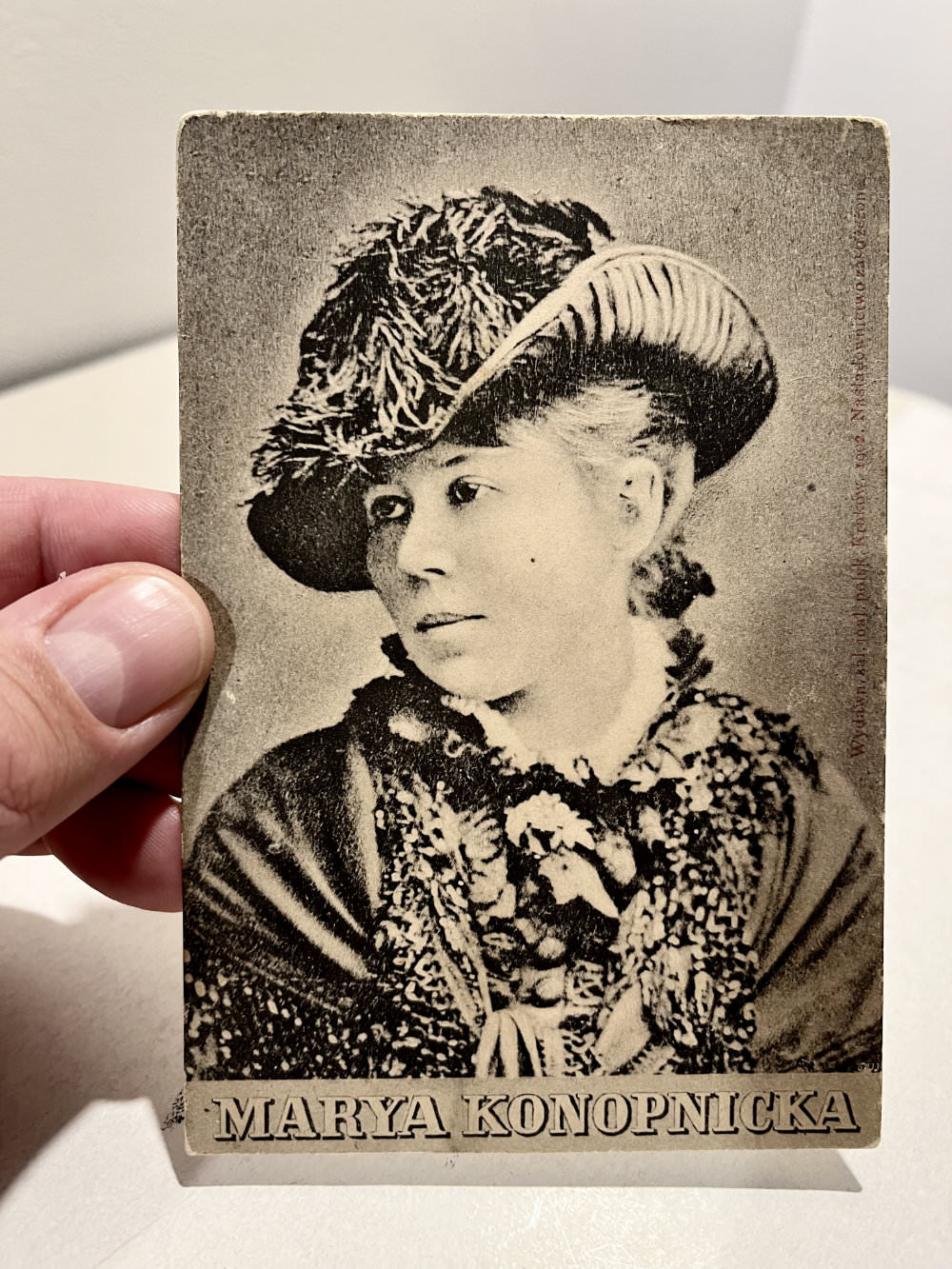

Visual artist and activist Karol Radziszewski and curator and arts writer Théo-Mario Coppola’s digital collaboration is a new commission from the LIAUX online platform. The lens- and text-based project consists of digital photographs of physical documents and objects from the Queer Archives Institute (QAI), and of an extensive interview between the two collaborators. QAI was founded by Karol Radziszewski as a self-managed archive documenting queer lives in several parts of the world, and has been regularly exhibited as part of his art practice. Working as a meta-archive, the online project considers the role of digital versions in the process of documenting.

The project is part of the Milano Digital Week 2022 programme.

An interview with Karol Radziszewski (KR)

by Théo-Mario Coppola (TMC)

September 2020 – November 2022

The situation in Poland is crazy right now. Having a rainbow symbol on you is enough to be attacked on the street. The number of queer teenagers who commit suicide is rising. The pressure of systemic homophobia is real.

Support from art institutions really depends on their directors – whether they’re afraid or not, and if they are prepared to risk their careers.

In 2020, the city-run Labirynth Gallery [Galeria Labirynt] in Lublin – a conservative city – staged the We Are People [„Jesteśmy ludźmi”] exhibition to protest against the government’s homophobic rhetoric. They risked losing budget funding by doing this, but they did it anyway.

Many other institutions have expressed their support – for example by adding a rainbow background to their logo – but have actually not done much.

When did you start developing artworks in relation to queer issues?

That was in the early 2000s.

The very first one I made was in 2002, while I was studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw [Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie]. It was a poster-like combination of two photos of my face with slogans quoting hate speech against minorities such as 'God Hates Fags' and 'God Loves Everyone, Even Niggers' written over it. I was frustrated with Polish homophobia and racism. I still am – even more so.

The solo exhibition Fags, which I had in a private apartment in Warsaw in 2005, was the first openly queer exhibition to take place in the country. While other Polish artists had shown works addressing these issues prior to the exhibition, it had never been as explicit.

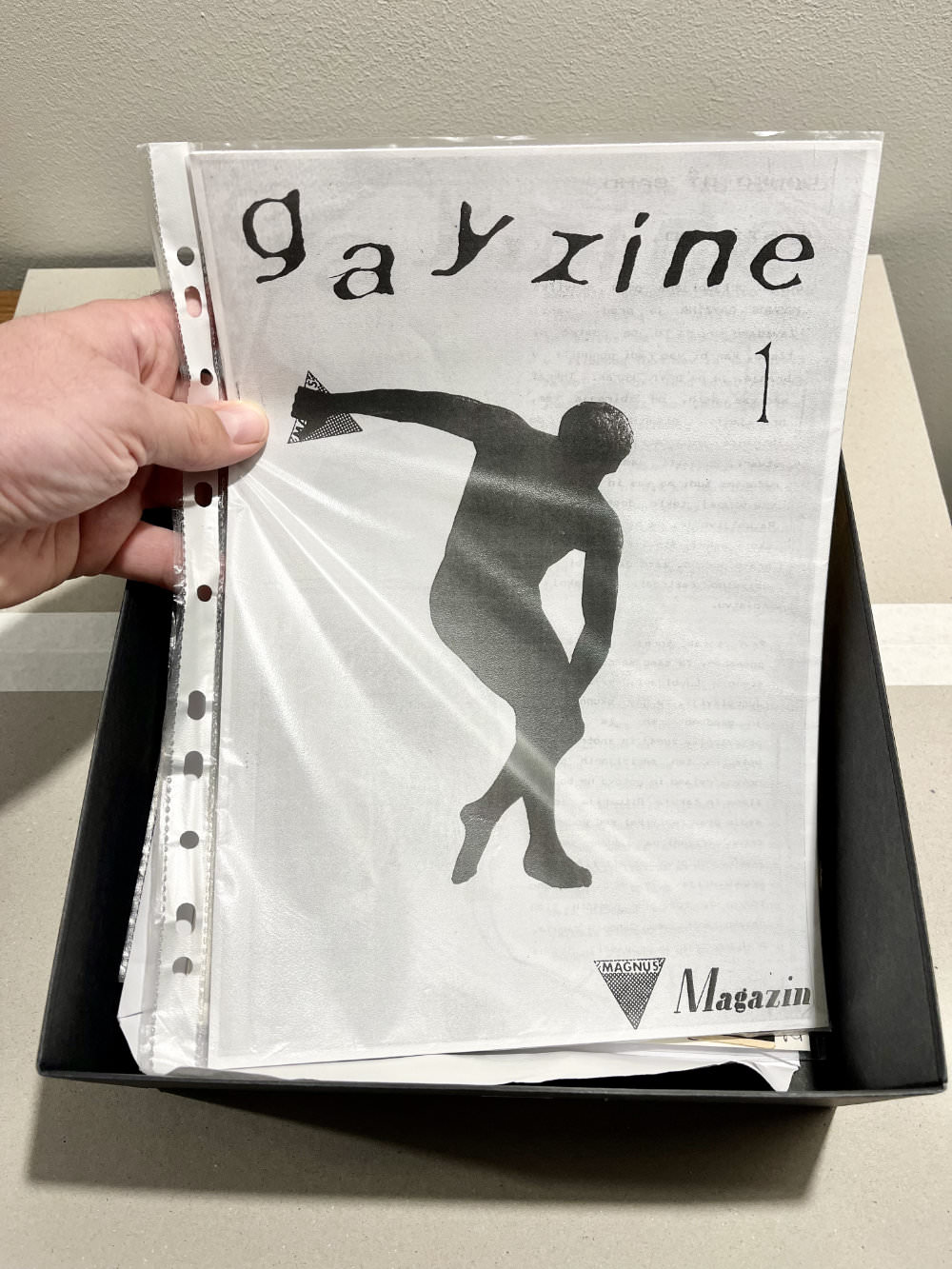

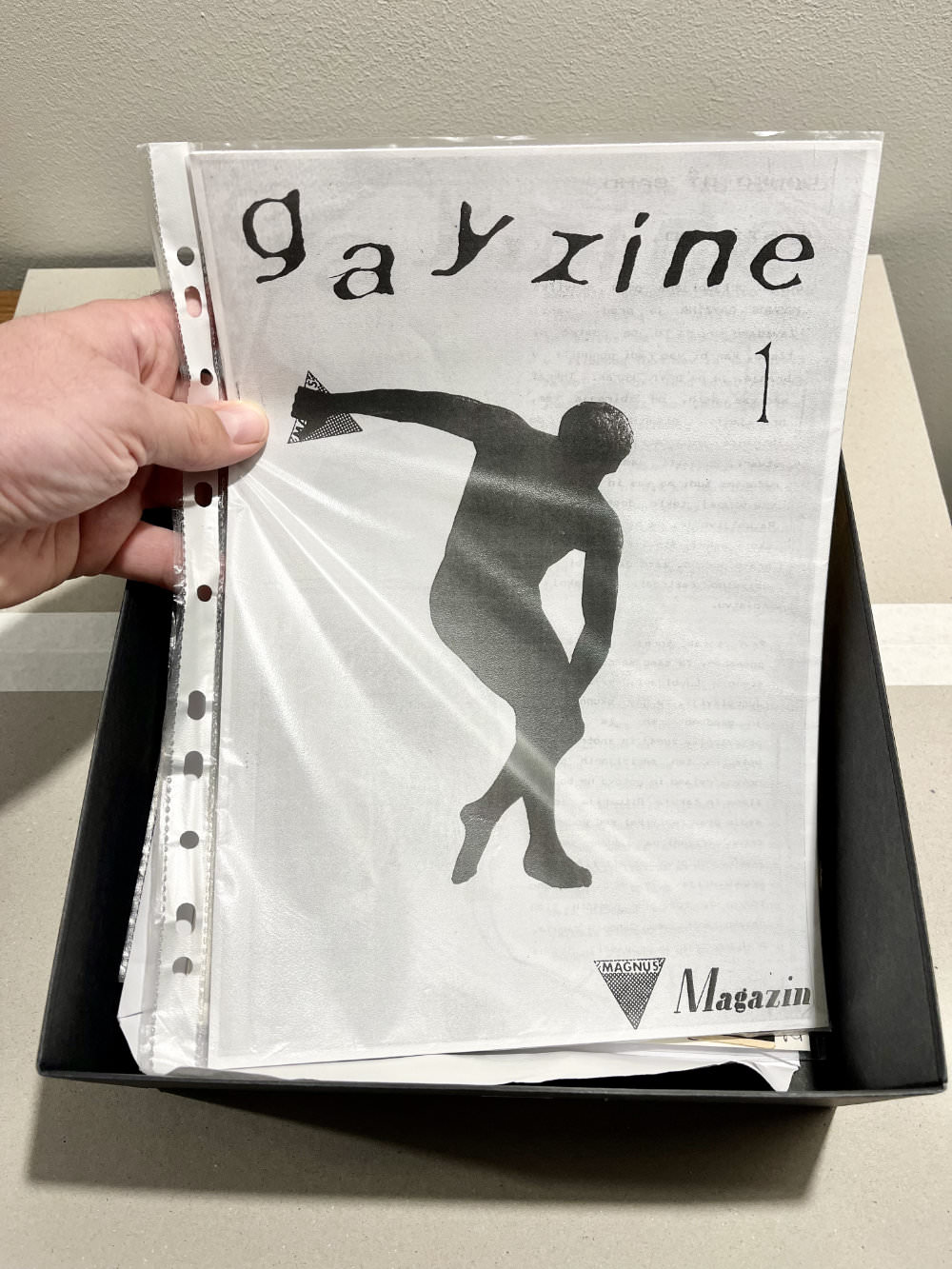

I started DIK Fagazine the same year, to set up the only Central and Eastern European art magazine devoted to masculinity and homosexuality.

Later I developed an archive-based practice and got more directly involved in process of queering institutions, of playing with the avant-garde canon and of questioning official art discourse.

As you mentioned, DIK Fagazine is the only art magazine of its kind to be published in Poland. What made you start a publication?

The first issue of DIK Fagazine was released at the beginning of 2005 and the magazine has been published on an irregular basis ever since. I was responding to the social situation around me, but also to my own coming out.

It was only after publishing a few issues that I became interested in history and started to explore archives. I wanted to learn about 'queer ancestors' and to sketch a wider panorama of Central and Eastern Europe, including the Czech Republic, Hungary, Estonia, Latvia, Serbia, and Romania.

The eighth issue, which is titled Before '89 and was published in 2011, was the result of an almost three-year-long research on homosexual life in the region before the Polish round table talks and the fall of the Berlin Wall. I interviewed many people about their doings in communist times, from cruising to activism.

With To Pee in a Bun, you blurred the boundaries between artistic and curatorial work. Do you consider curating to be an extension of your art practice?

That’s a project I made in 2009, when I acted as curator for the first time, by organising a show that featured dozens of works from the Zachęta National Gallery of Art [Zachęta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki]’s collection in Warsaw. The show was full of irony and the curatorial text was basically an interview with myself, under the guise of a young artist schizophrenically arguing with a young curator.

It was a way for me to raise questions about museum policy, about the history of a collection that was built under communism, and about the roles of both artists and curators.

Later curatorial practice became one of my regular tools, especially when I started to exhibit the Queer Archives Institute’s collections.

What is the Queer Archives Institute (QAI)?

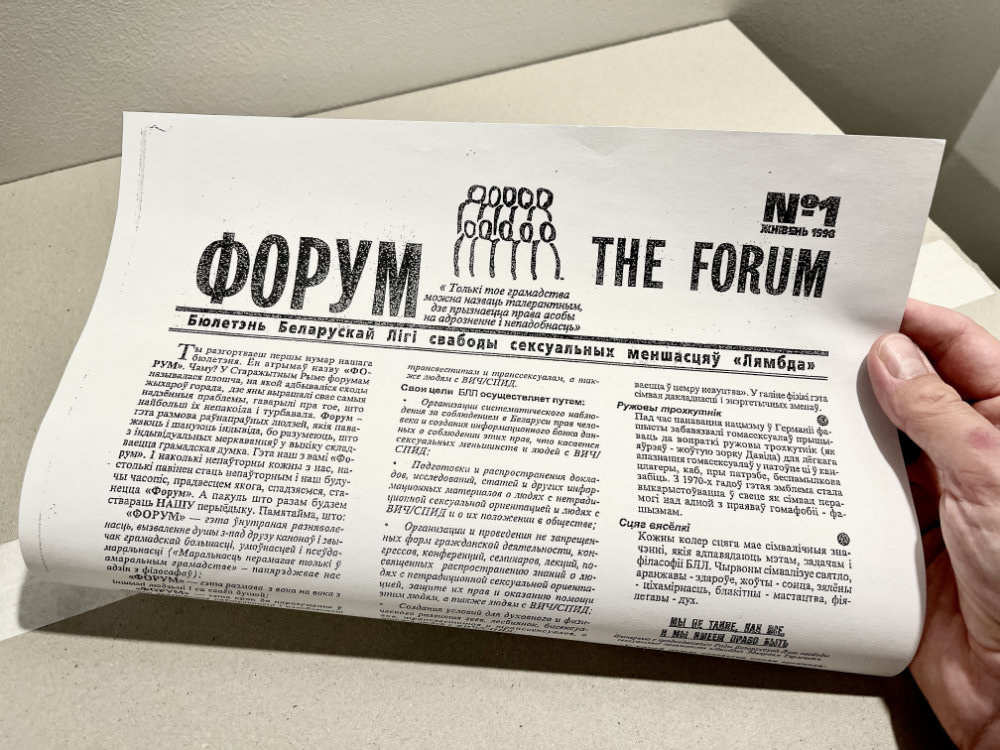

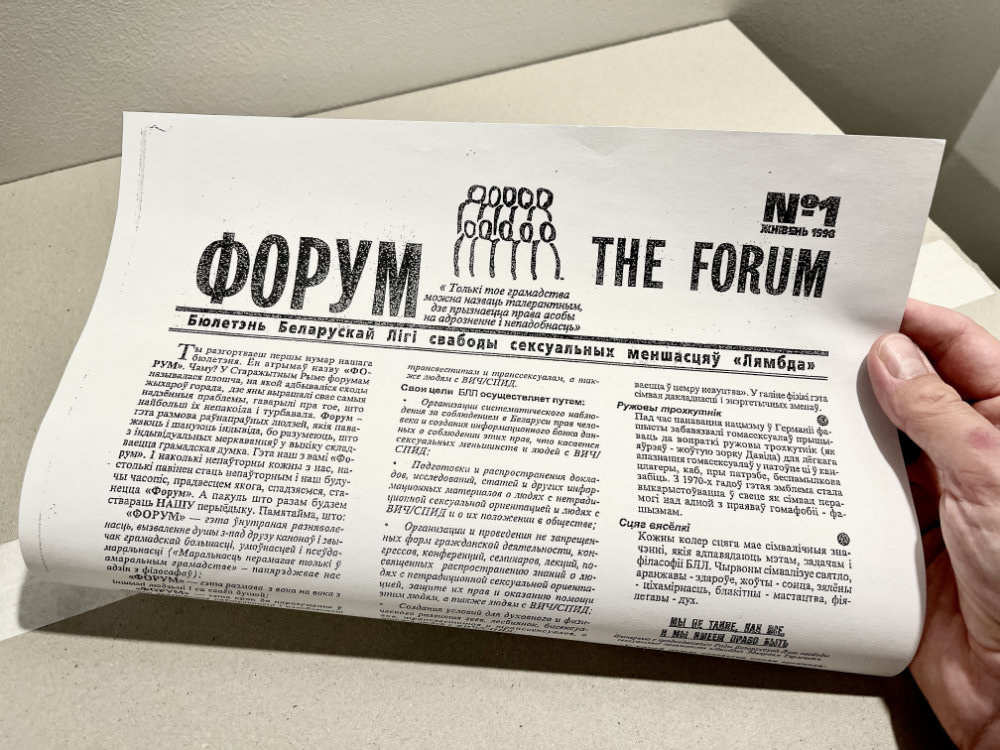

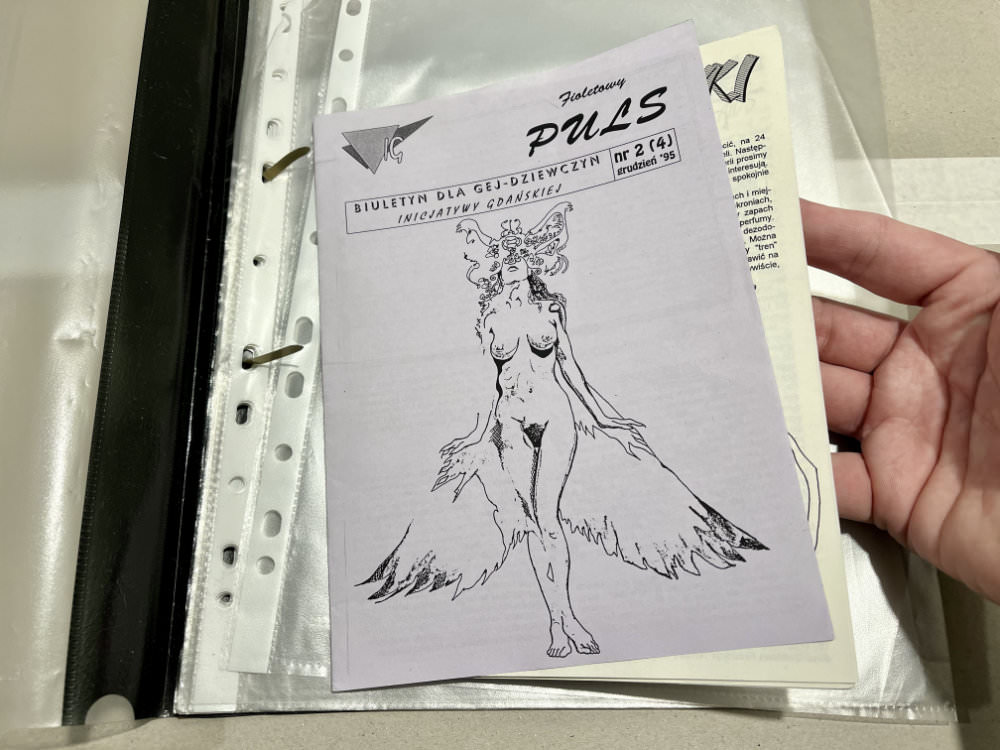

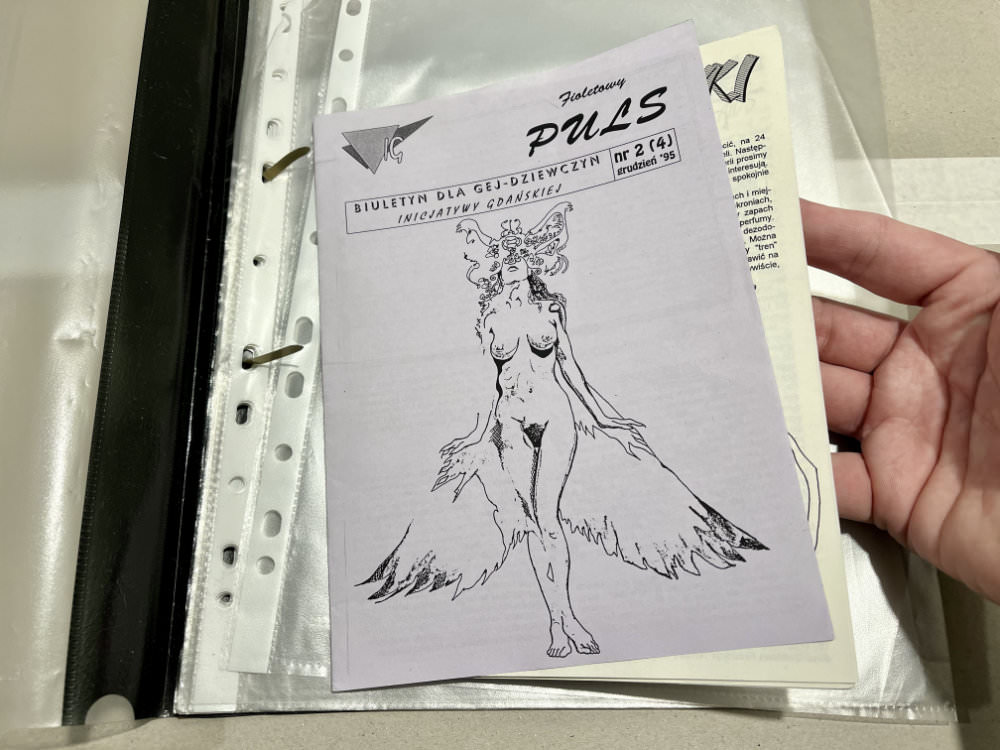

QAI was conceived as a not-for-profit organisation engaged in researching, collecting, digitising, presenting, displaying, analysing and interpretating queer archives from an artistic perspective. It focuses on introducing early publications, culture and activist events, and on providing historical context.

I established QAI on 15 November 2015, to mark the thirtieth anniversary of a repressive operation against suspected homosexuals in Poland that was called Operation Hyacinth [Akcja „Hiacynt”]. The operation was led by the communist police, known as Citizens' Militia [Milicja Obywatelska], and resulted in the registering of around 11000 personal files between 1985 and 1987.

The documents and objects in the collections primarily come from countries of the former Eastern Bloc. Some of them were donated. Some were bought, especially when the purchase was a way of supporting others. But the most unique and interesting way was when they were exchanged with other activist-run archives like Forum Queer Archive Munich [Forum Queeres Archiv München] in Germany or the Lesbian Library & Archive [Lezbična knjižnica] in Slovenia.

I also exchanged artworks with artists.

Do items enter the collections separately or as archives that have already been sorted?

It’s mostly individual items. When it’s archives, they are usually not organised but rather in a chaotic state – the exception being Ryszard Kisiel’s.

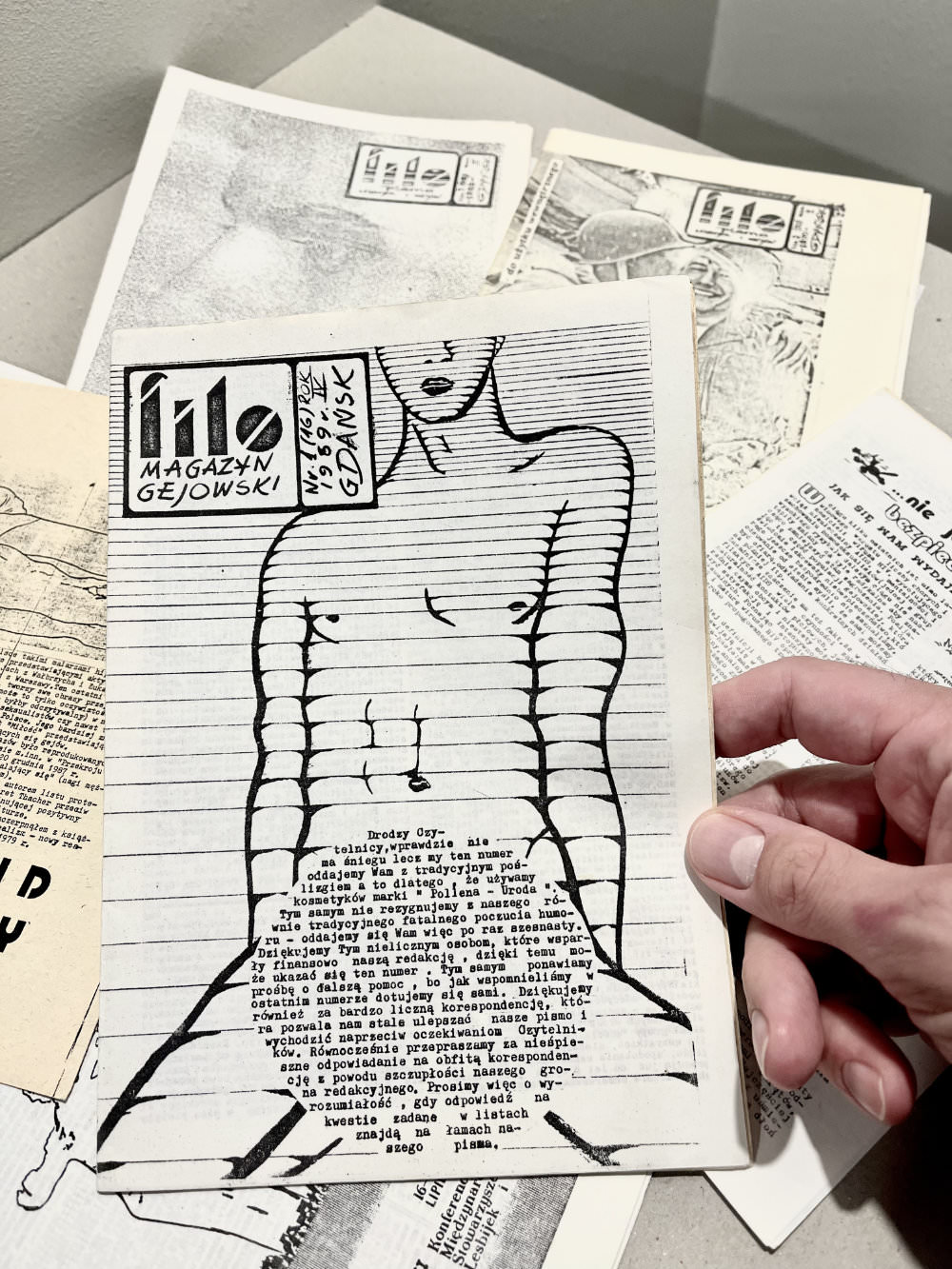

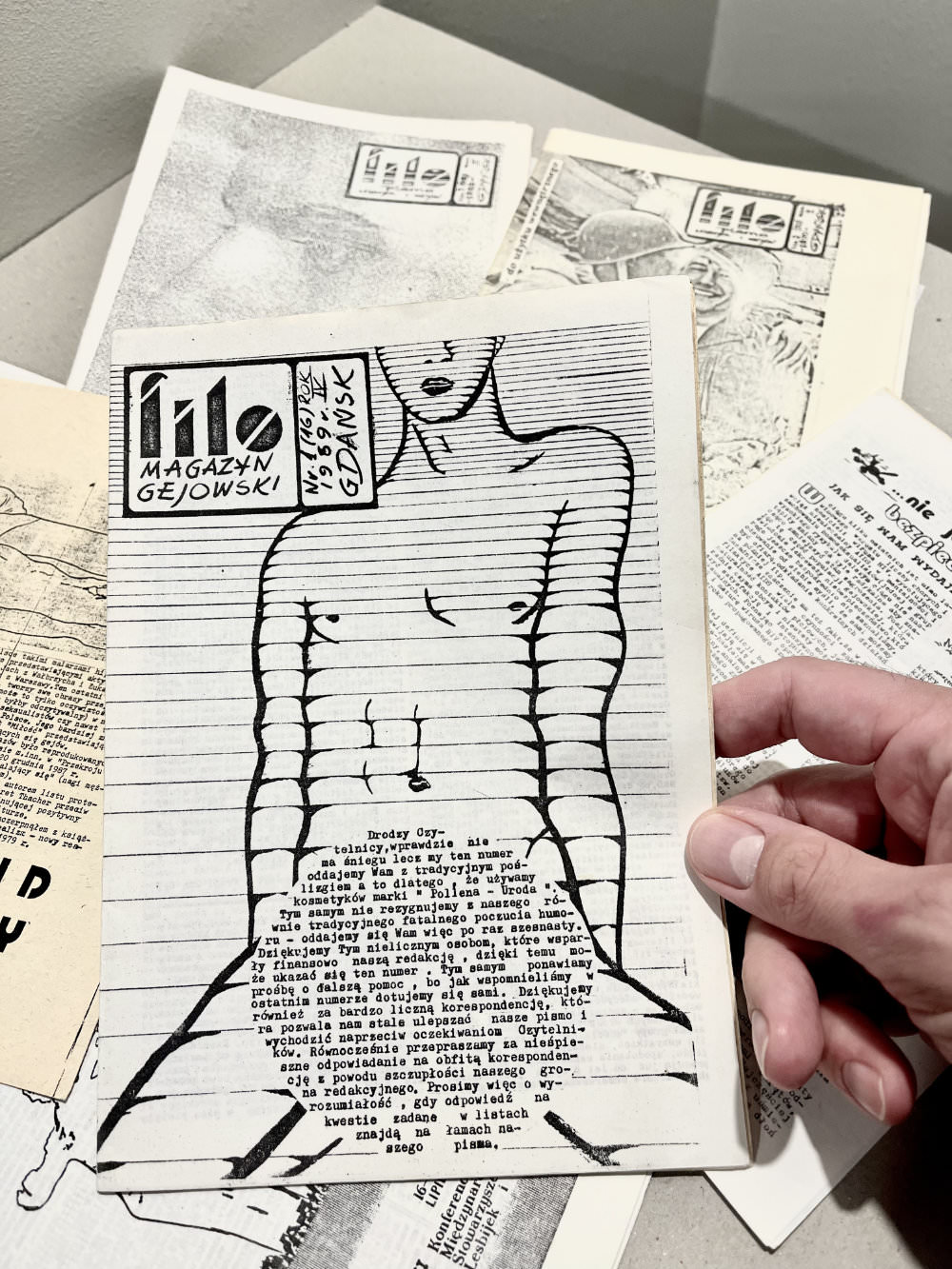

Ryszard, with whom I have been working since 2009, is an amateur photographer. He founded the Polish gay zine Filo in 1986. Filo was published as a direct reaction to Operation Hyacinth. It was one of the first queer publications to come out of Central-Eastern Europe. It was distributed semi legally and among friends until 1989, and later transformed into a regular magazine.

Ryszard passed pre-selected parts of his archive on to me that we later tried to organise and contextualise together.

When not on view, how are the collections arranged? Do you use a classification system?

I’m struggling with classification and haven’t reached the point where a clear way of doing it would appear. The very basic and handful system that I use is to gather materials according to the countries they relate to, even if I mix them all up afterwards when they’re exhibited.

How are the collections delineated in geographical and historical terms? Did the collections’ delineation change through time?

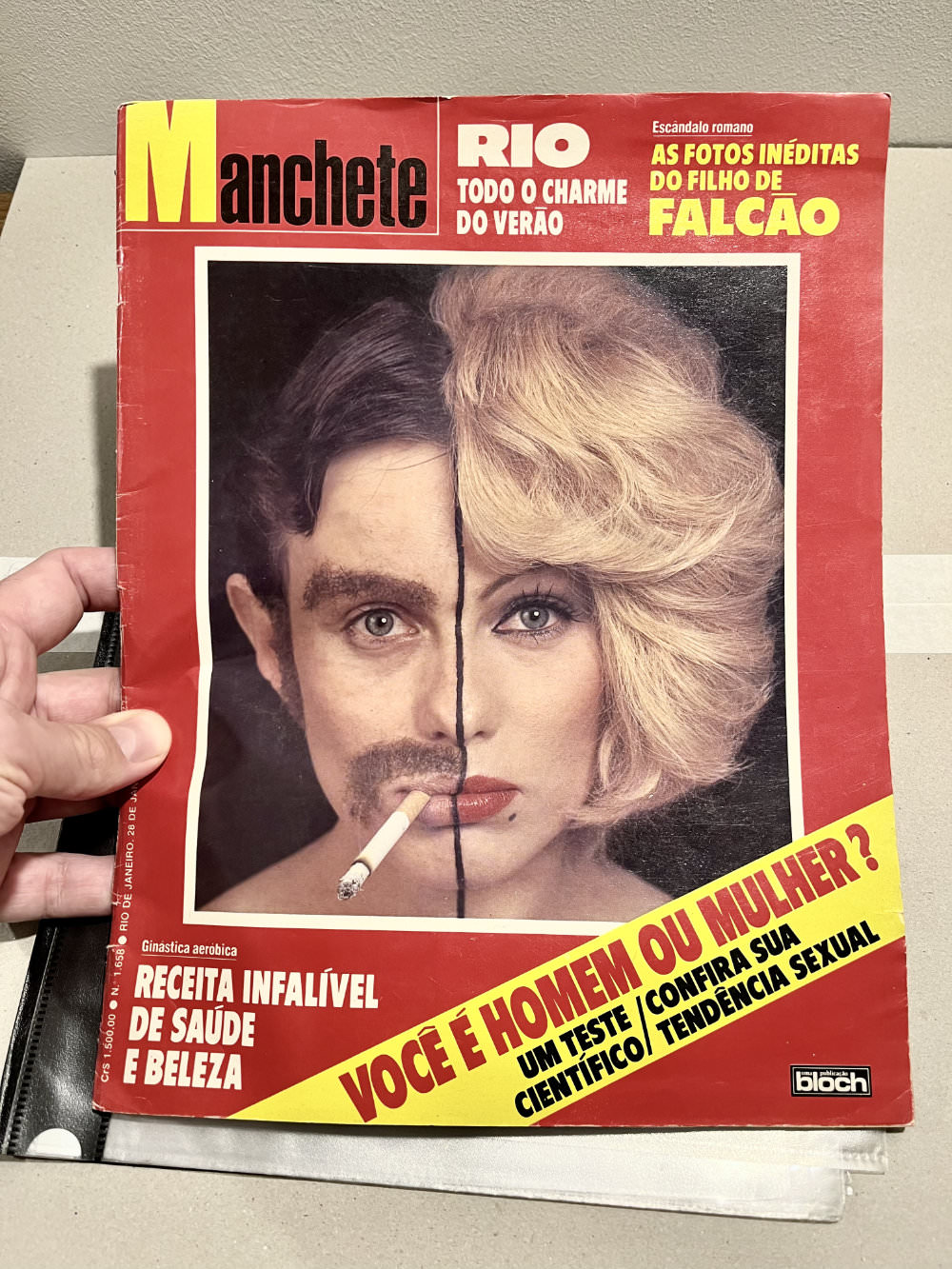

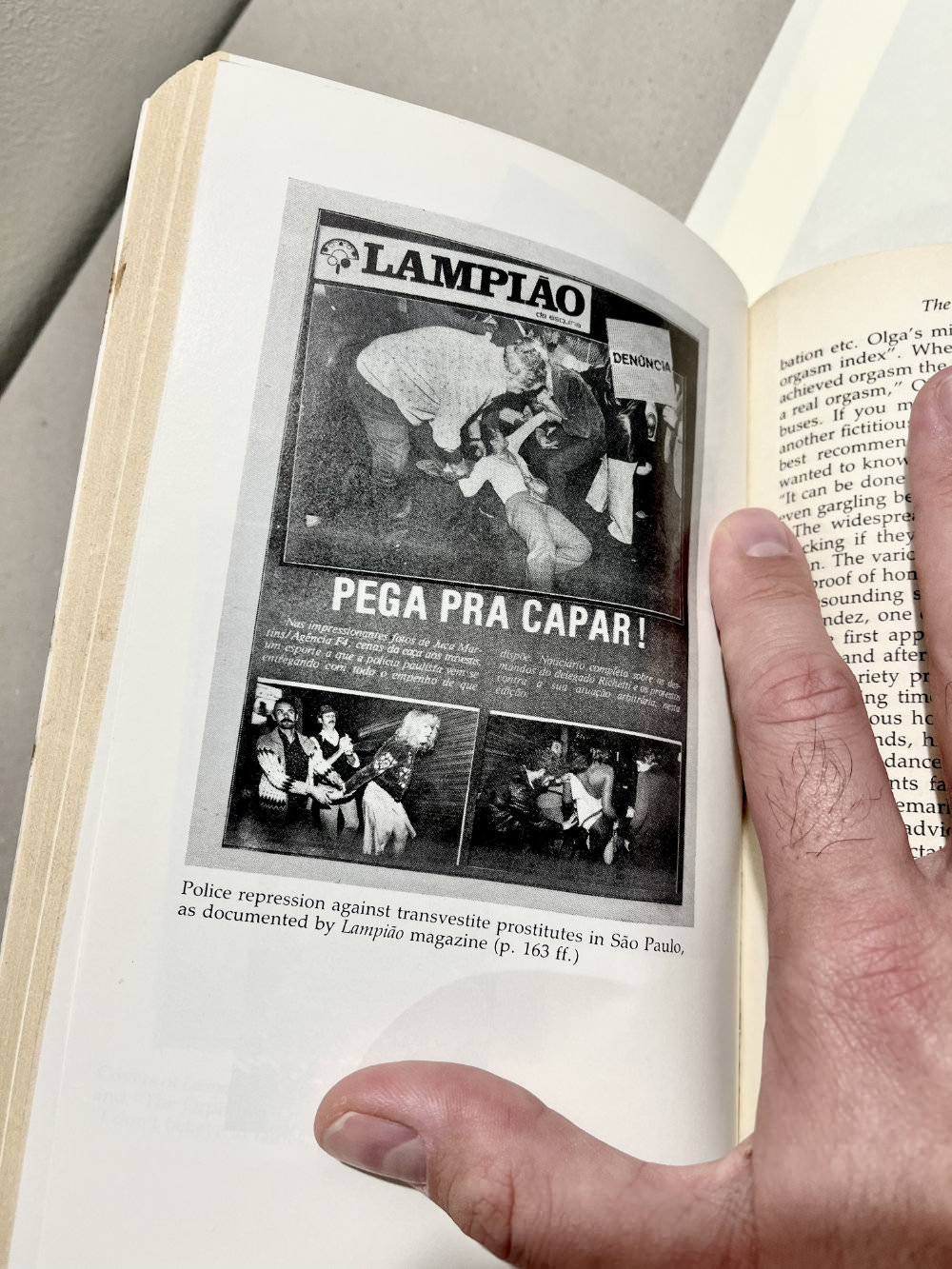

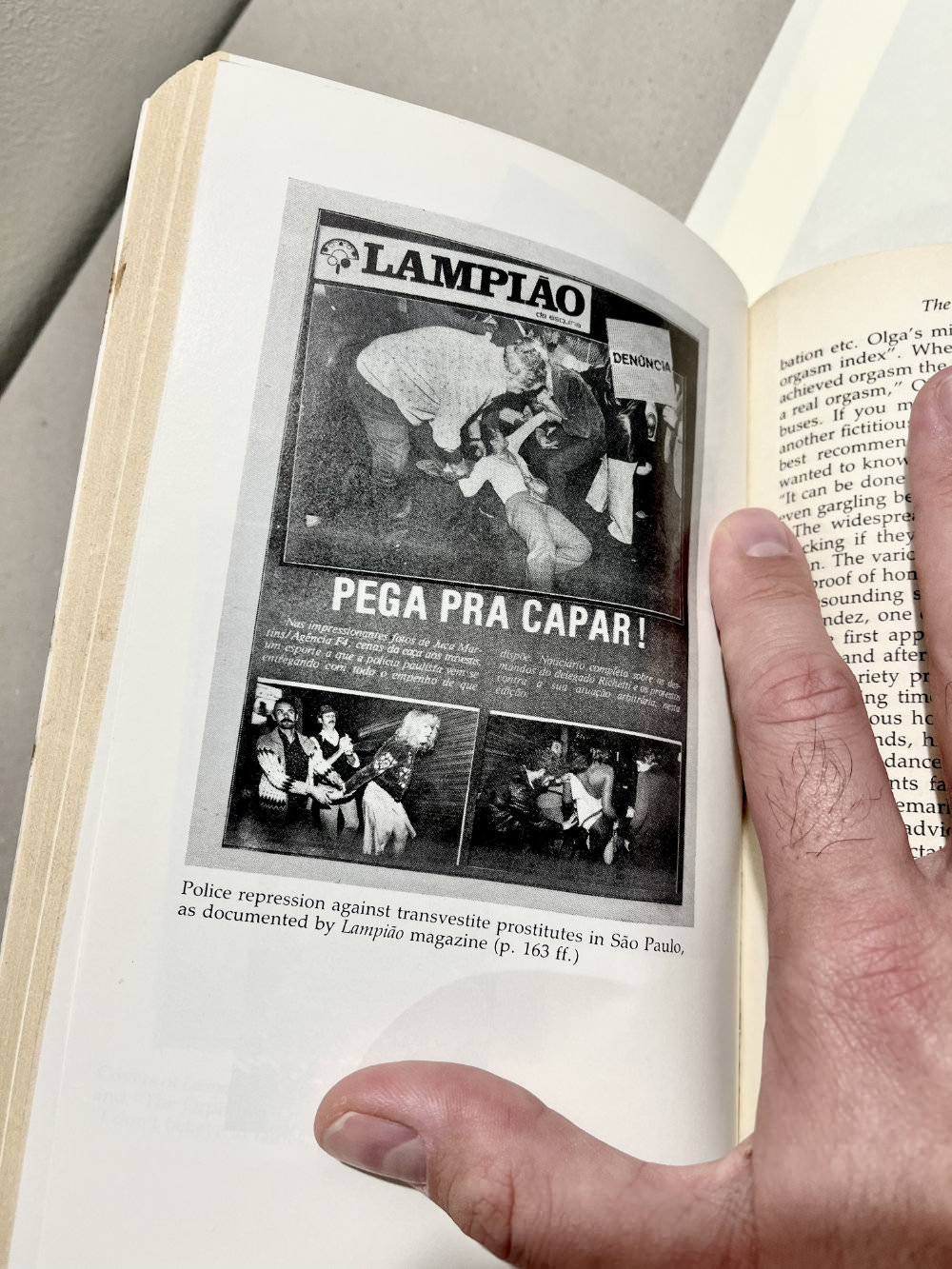

The natural beginning was Poland and the 1970s and 1980s – during communist times. It evolved to neighbouring countries like Ukraine and the Czech Republic, and then beyond Central and Eastern Europe to include countries like Brazil or Columbia. But the focus was still on the second half of the 20th century.

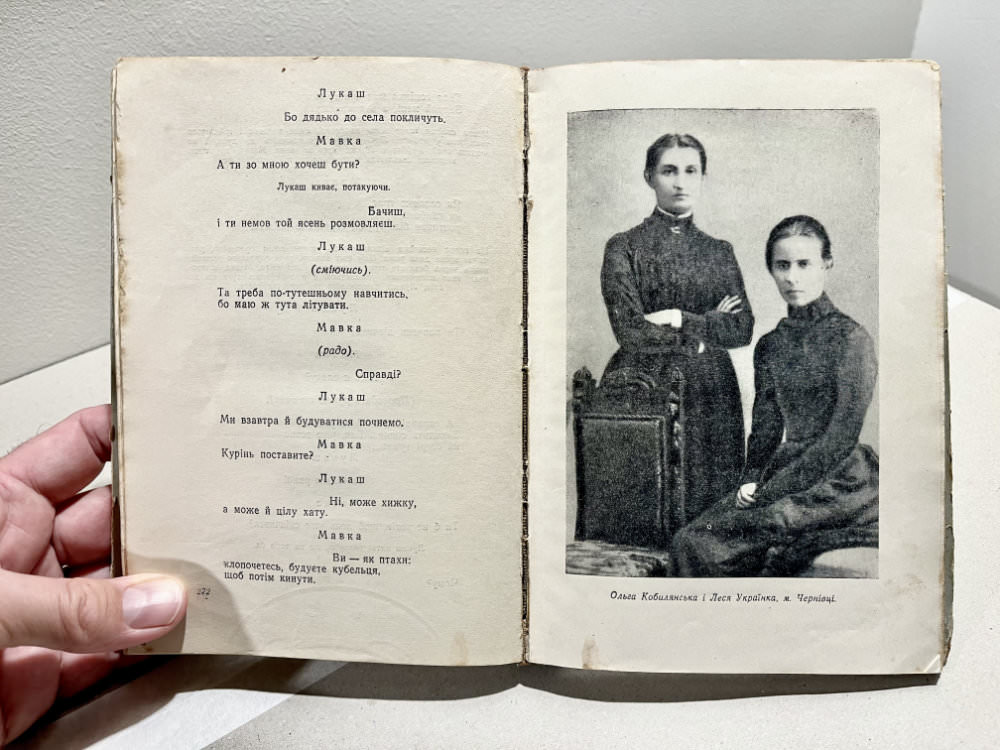

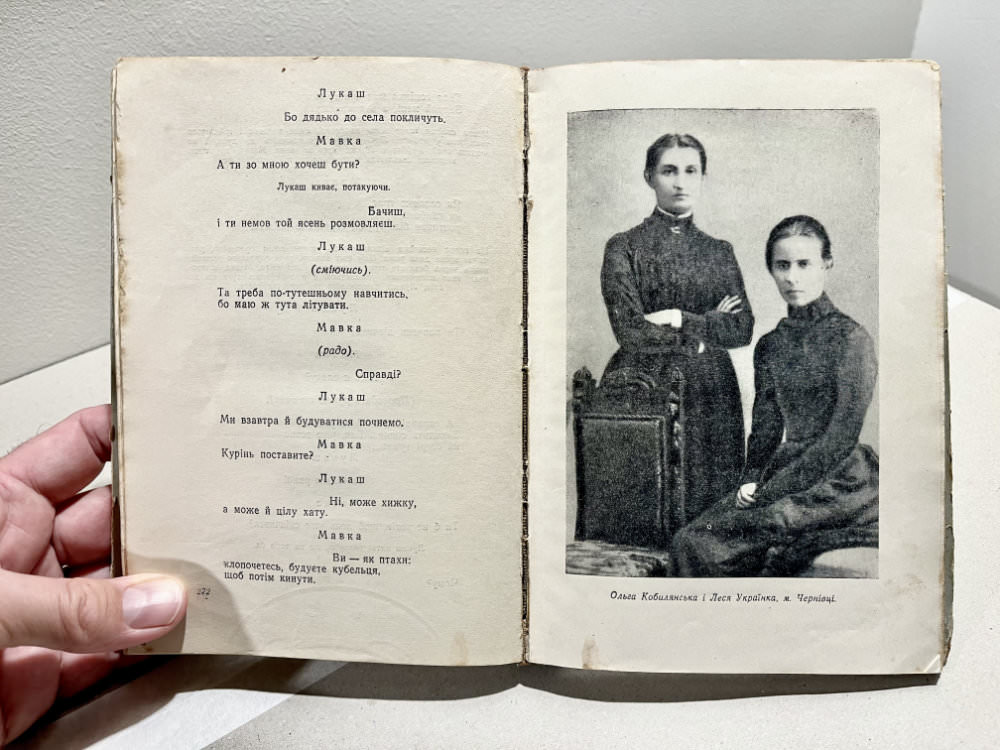

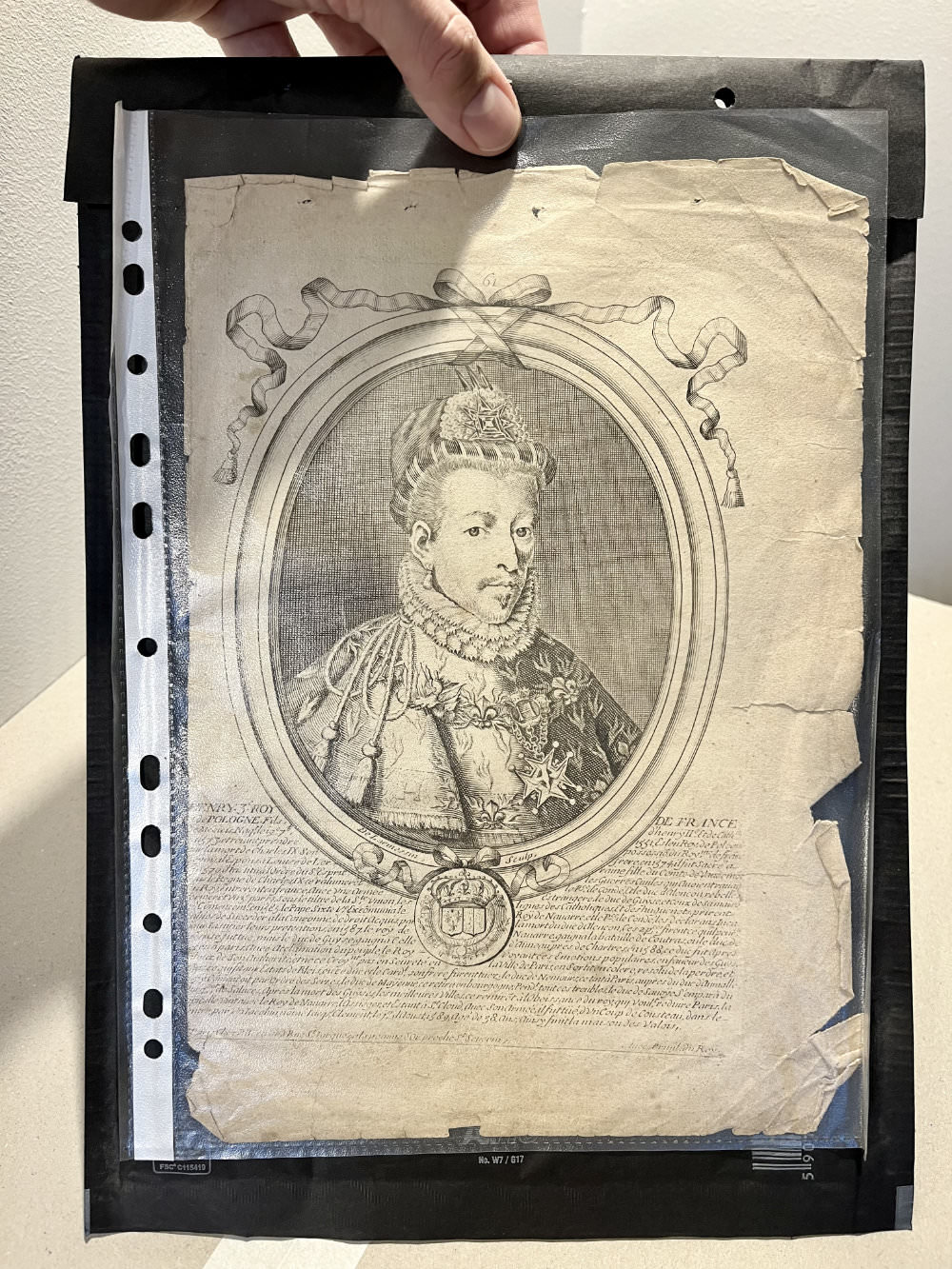

Only recently did I start to work with historians and art historians and try to delve deeper into the past, to include the 19th or even earlier centuries. This is more playful in a way – not to have only dry testimonies but also to play with the museums’ way of collecting objects. Like when I purchased the 17th-century engraved portrait of Henry III, the first elected Polish king who was down for cross-dressing and having relations with both men and women.

Among the projects you have developed with QAI, there was an exhibition in Brazil titled Queer Archives Institute. Could you introduce this particular project?

That was the exhibition that inaugurated the institute’s activities. It was held in 2016 at the Videobrasil headquarters in São Paulo. The exhibition display implied that a new institution had opened on a temporary site, but also determined QAI’s characteristic working method – using exhibition design to occupy, to appropriate and to queer an existing art institution and its collection. This included a large-scale QAI logo on the wall and large glass display tables.

The tables featured materials from both Brazil and Central and Eastern Europe. The materials were organised around themes such as 'AIDS', 'pioneering queer publications', 'lesbians', 'nudist beaches', and 'gender'. The themes were supposed to simulate future possibilities for browsing digitized resources with the use of keywords.

To set the exhibition in Brazil and to show materials from the country indicated a broader scope of interest than the hitherto-researched former Eastern Bloc states. The decision to combine archival materials in this way was to generate new meanings, but above all to defy nationalistic expectations that confine heritages to strictly national narratives. The search for common denominators between geographically remote regions pointed out to the supranational dimension of queerness and became a particularly important aspect of QAI.

How have the exploration and the presentation of archives through QAI made you reflect on alternative narratives?

Post-socialist states, where many historical threads have been broken or, in fact, never actually emerged, are witnessing attempts to construct national identities and narratives anew. History, including art history, has largely been reconstructed and has sometimes been manipulated to fit to political agendas.

I take special interest in artistic strategies that provide means to actively respond to these processes. I am interested in reviewing history, in rewriting it from a queer perspective and in complementing main narratives with neglected threads, in particular from minority voices.

You have explored the memory of subversive and queer lives in museums and other art institutions. What processes does QAI use to reshape the historicising of art practices in institutional context?

QAI sometimes literally adopts a performative form, as with the action QAI/MSU at the Museum of Contemporary Art [Muzej suvremene umjetnosti, or MSU] in Zagreb. I interacted with visitors while wearing drag, inside a part of the museum exhibition that I had appropriated to transform it into a temporary QAI office. It was part of a larger project to 'queer' the museum.

I stayed in a museum building right beside the museum archive for a month, to conduct an artistic investigation of sorts by looking behind the scenes. The investigation revealed the strategies of collection building, the process of creating and interpretating specific works, and the personal influence of current and former museum employees on the programme.

The result was published as the tenth issue of DIK Fagazine under the title Zagreb – Queering the Museum. As QAI is a kind of an umbrella for all my archive-related projects, this issue was naturally made a part of it. The idea was that, from then on, the magazine would publish my research findings and QAI would become the publisher.

In 2020, the QAI/RO exhibition at the National Museum of Contemporary Art [Muzeul Național de Artă Contemporană, or MNAC] in Bucharest summarised my research on queer Romania, as did the accompanying book.

How do you see QAI evolving?

QAI is a long-term project open to international collaboration with artists, activists and academics. It is the biggest project I have done, and it encompasses the different aspects of my research so far.

The new strategy I’m pursuing is to diversify the collections and to actively create an archive for the future. To complete QAI with voices and representations that have not been included yet.

I have been working with oral history for more than ten years. I'm now trying to document transgender voices.

As for the collection of artworks, my focus is on non-heteronormative women and non-binary persons. The items are sometimes very recent – like the zines or photography series by a younger generation of female artists who are just entering the scene.

Alberto Arlandi